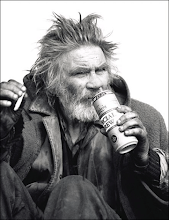

My grandfather was a wonderful storyteller. I spent many a winter’s evening sitting on the floor in front of a roaring coal fire as he looked down at me from his brown leather armchair. The red-yellow, flickering light from the flames lit up his long, wrinkled face in the darkened room. His one good eye glistened animatedly while the other stared straight ahead, lifeless and sinister. His whole appearance emitted an eerie sense of menace as he told me in exquisite detail how, as a mere seventeen year old, he fought hand-to-hand combat with a German soldier for more than an hour before, completely exhausted, they both crawled off in opposite directions through the mud and water and blood of Flanders.

My grandfather instinctively knew how to scare me with his stories, just enough to make the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end, but always at the same time making me feel safe and secure in his care, like flying with both fear and exhilaration through the night sky under his strong and reassuring grasp.

My grandfather’s name was Thomas Duffy. I called him Granda. My grandmother’s name was Elizabeth, née Renwick. I called her Nana.

My Granda was born in Drogheda on 14th February 1898, St Valentine’s Day. My Nana was born in Gateshead on 21st April 1905, an ordinary Tuesday. Soon after his father, my great grandfather, died of Tuberculosis, my Granda moved to Motherwell at the age of six with his mother Margaret, to live with her brother, my Granda’s uncle Patrick and Patrick’s wife, my Granda’s auntie Bridget.

My Granda lost his left eye during the Great War. He told me how, with his right eye, he last saw his left eye as it dangled from the end of a bayonet being held by another German soldier, who was apparently frozen in terror at the sight of my Granda’s eye hanging there in front of his own eyes, looking at him unforgiving and unblinking, dripping with blood. The German soldier stood screaming for several seconds before a bullet caught him on the right shoulder, knocking him to the ground. He screamed no more and my Granda once again escaped with his life, and my future, intact. Later he confessed to me that he could not possibly have witnessed the horrific scene as he was unconscious throughout, and put his robust memory of it down to the great and gory detail in which it was described to him by his comrades as he lay in the field hospital, his veins flowing with morphine.

Nurse Renwick tended to my Granda back in the field hospital before he was shipped back to Scotland, where he was delivered unto the care of his mother. After the war, nurse Renwick returned to Gateshead and decided to visit my Granda in Motherwell. He had given her his address before escaping from the madness and mayhem. They were married within the year, my uncle Tommy already on the way.

My Granda felt betrayed by the country he had served so bravely and at such a cost, as he was left to his own devices with a badly infected wound which took eighteen months to clear. It was three years before he was afforded the luxury of a false eye made of balsa wood and crudely painted. He told me how it was cold and uncomfortable, though much better than the ugly, gaping hole or the eye patch which frightened the lieges. Women and boys alike would turn and flee, and men would cross the street at the sight of his approaching.

“I sometimes think o thon German soldier,” he once told me. “The wan I had the fight wi. Did he survive the war? Is he still alive the day? Could he be sittin doon right noo somewhere in Bavaria, telling his ain grandchildren how he fought for an hour wi a crazy British sojur?”

His eye glazed over as he stared into the fire. I think I saw him wipe away a tear but I said nothing and I too gazed into the fire.

“Such a waste,” he whispered. “Such a waste ae gid young lives.”

To me, my Granda was a hero.

When I was twelve, I was playing football with my fellow street urchins one warm Sunday evening when I spotted him walking along the street with that familiar stoop and his hands clasped behind his back. He sported the usual battered old bunnet and worn-out hounds tooth jacket as he walked slowly and nonchalantly, seemingly without a care in the world. I called out his name and he stopped and, on recognising me, raised his arm to wave. He stood for some minutes watching the game, occasionally shouting words of encouragement.

“Good baw Thomas . . . gae it tae Thomas . . . great goal Thomas . . .”

At half-time I went over to speak to him.

“Are ye gaun tae oor hoose Granda?”

I wiped beads of perspiration from my face.

“Naw son,” he replied. “Jist oot furra walk n a bit ae fresh air.”

He pulled a white paper bag from his pocket and held it towards me.

“Hiv a mint Thomas.”

“Aw ta Granda.”

He always carried a supply of rock hard white mints.

“Ye lookin furrit tae Hampden oan Setterday then?” he said, after waiting for his dentures to negotiate the hard sweet.

“Aye Granda, a cannae wait. Ma first cup final.”

“A can still remember ma first final.”

He looked at his feet and shook his head as he spoke.

“Celtic’n Rangers it wiz. A well remember no bein able tae sleep the night afore, a bit like yersel Thomas.”

“Am glad it’s Dunfermline no Rangers this time,” I said. “Mum widnae lit me go if it wiz Rangers.”

“Aye it’s a shame aw this bigotry nonsense still goes on. A wish they could enjoy the rivalry withoot aw that baggage. Ach well, that’s religion fur ye. Mair folks’ve died oer the heid ae religion than onythin else in this world ah’ll tell ye.”

My friends were now preparing to resume the match.

“A better git movin,” I told him.

“Aye, ah’ll away then Thomas,” he said. “See ye soon then.”

“Aye, see ye Granda. Take care.”

I moved towards my friends but was stopped in my tracks.

“Jist a wee minute Thomas,” he called after me and I turned to face him once again.

“Whit is it Granda?”

“If onybody asks,” he said. “If yer Nana asks like . . . well . . . ye never seen me, right?”

I looked at him in silence.

“If Nana says onythin, don’t lit ona ye seen me, right?”

“Sure Granda, a wullnae say a word.”

I didn’t ask for an explanation but he offered me one anyway.

“It’s jist that, ah’m supposed tae be it six o’clock Mass. Couldnae be bothered gaun. She’ll gae me merry hell if she funs oot.”

“Nae problem Granda,” I reassured him. “She’ll no hear it fae me.”

“Good lad,” he smiled warmly. “Go on then. Enjoy yer gemme.”

I felt a great surge of pride in the realisation that my Granda, the great hero, had shared a secret with me and that my silence would protect him from a nagging, or worse. At the same time I wondered how it was that my Granda, who had fought hand-to-hand combat with a German soldier for more than an hour; who had lost an eye under the piercing blow of a German bayonet; who had stood up to the Protestant gangs who stoned him and his family as they walked to Mass every Sunday morning in Edwardian Motherwell; who had stood shoulder to shoulder with his fellow workers and battled with the riot police during the General Strike; how could this great hero be walking the streets alone, rather than tell his wife, my Nana, that he couldn’t be bothered going to Mass?

Three years later, just days after my Nana’s funeral, my Granda was telling me what a wonderful and strong woman she was. For the first time I asked him about that Sunday night and he told me he remembered it well.

“A bet ye were wonderin why a couldnae jist tell ur a wisnae gaun tae the chapel.”

I admitted that the thought had crossed my mind.

“When ye git tae oor age Thomas, me n yer Nana a mean. When ye git tae oor age, ye start thinkin aboot death n'at. No the actual dyin. No, a mean the passin oan, ye know, whit’s waitin fur ye oan the other side.”

“Like Heaven n Hell?”

“Aye, that’s right. It’s jist that, a havnae believed ony ay it since a wiz your age.”

“Ye mean ye don’t believe in God?”

“Well, it’s no as simple as that. It’s jist this gaun tae Mass oan a Sunday thing. A jist don’t think it’s such a big deal if ye decide tae gae it a miss noo n again. Bit tae listen tae yer Nana, it wiz hellfire n eternal damnation fur me if a so much as mentioned stayin in the hoose when a should be tt the chapel. The thing is Thomas, she believed in it aw the way, an if a committed a mortal sin, as she seen it like, bay missin Mass, she’d jist worry herself sick that ah’d drap doon deid n go tae Hell before a hud the chance tae go tae confession or change ma underpants. She even telt me ah’d spoil it fur hur cos she’d go tae Heaven n couldnae enjoy it knowin a wiz burnin away in the Bad Fire.”

“So ye don’t believe in the Bad Fire eether?”

“Mibbe there is a Bad Fire, mibbe no Thomas, bit if there is, a cannae believe God wid pit some'dy there jist fur missin Mass oan a Sunday. Bank robbers n murderers aye, bit no fur missin Mass or tellin the odd white lie or usin bad language or stealin a loaf ae breed or, or whitever. Surely the God Nana an yer mother worship every Sunday cannae be that cruel.”

To me, my Granda was now a hero and a sinner.

“So ye preferred a quiet life rather than upset her.”

“Aye Thomas, that’s it exactly,” he said with a smile. “That n the fact she wiz English intae the bargain.”

My Granda was a great Rabbie Burns fanatic. He could, and often did, recite the whole of Tam O’Shanter from start to finish. Though he was a Burns fanatic, he wasn’t boring with it, and didn’t ram it down our throats. He would quote the great man in everyday life and always in proper context.

My friend Owen Kelly and I spent hours preparing for the school Christmas dance. Our Lady’s High School was an all-boys establishment, a legacy of the traditional thinking of the Catholic hierarchy in the first half of the twentieth Century. The more intelligent Catholic boys were not to be distracted from their education by the testosterone challenging proximity of girls in the classroom. So the annual arrangement was that girls from the Catholic Convent School would be bussed in for the evening, lest we should be tempted by the apparently greater evil of dancing with boys.

As I stood before my mother and my Nana, my curly hair caked in brylcreem in a fruitless attempt at straightening it in defiance of the laws of both physics and physiology; my winkle-picker shoes shining proudly following their first polishing since the previous Christmas; my face and neck blotchy red and stinging under the cheap and malodorous after shave; and the top three buttons of my shirt unfastened to reveal an expanse of scrawny white skin under the merest sprinkling of fluffy chest hair, I felt like I was being briefed in advance of a dangerous and important mission.

“Button your shirt up Thomas or you’ll catch the death of cold.”

“Comb your hair Thomas. It’s sticking up at the back.”

“Don’t let any of those Convent lassies drag you out the school.”

Chance would be a fine thing.

“And if they kiss you, keep your mouth shut.”

No fear. If I get kissed, I’ll not be telling any of you lot.

They started prodding me, tugging at my collar, buttoning my shirt, patting my hair.

“What’s wrong with curls anyway Thomas? You shouldn’t try and hide them.”

“Aye, it doesn’t look natural son.”

Oh wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

Tae see oursels as others see us !

Quoth Granda from behind his Motherwell Times.

“Just you read your paper and mind your own business,” said Nana.

“And don’t be late Thomas. Don’t get carried away and miss the last bus.”

We think na on the lang Scots miles,

The mosses, waters, slaps and styles,

My grandfather instinctively knew how to scare me with his stories, just enough to make the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end, but always at the same time making me feel safe and secure in his care, like flying with both fear and exhilaration through the night sky under his strong and reassuring grasp.

My grandfather’s name was Thomas Duffy. I called him Granda. My grandmother’s name was Elizabeth, née Renwick. I called her Nana.

My Granda was born in Drogheda on 14th February 1898, St Valentine’s Day. My Nana was born in Gateshead on 21st April 1905, an ordinary Tuesday. Soon after his father, my great grandfather, died of Tuberculosis, my Granda moved to Motherwell at the age of six with his mother Margaret, to live with her brother, my Granda’s uncle Patrick and Patrick’s wife, my Granda’s auntie Bridget.

My Granda lost his left eye during the Great War. He told me how, with his right eye, he last saw his left eye as it dangled from the end of a bayonet being held by another German soldier, who was apparently frozen in terror at the sight of my Granda’s eye hanging there in front of his own eyes, looking at him unforgiving and unblinking, dripping with blood. The German soldier stood screaming for several seconds before a bullet caught him on the right shoulder, knocking him to the ground. He screamed no more and my Granda once again escaped with his life, and my future, intact. Later he confessed to me that he could not possibly have witnessed the horrific scene as he was unconscious throughout, and put his robust memory of it down to the great and gory detail in which it was described to him by his comrades as he lay in the field hospital, his veins flowing with morphine.

Nurse Renwick tended to my Granda back in the field hospital before he was shipped back to Scotland, where he was delivered unto the care of his mother. After the war, nurse Renwick returned to Gateshead and decided to visit my Granda in Motherwell. He had given her his address before escaping from the madness and mayhem. They were married within the year, my uncle Tommy already on the way.

My Granda felt betrayed by the country he had served so bravely and at such a cost, as he was left to his own devices with a badly infected wound which took eighteen months to clear. It was three years before he was afforded the luxury of a false eye made of balsa wood and crudely painted. He told me how it was cold and uncomfortable, though much better than the ugly, gaping hole or the eye patch which frightened the lieges. Women and boys alike would turn and flee, and men would cross the street at the sight of his approaching.

“I sometimes think o thon German soldier,” he once told me. “The wan I had the fight wi. Did he survive the war? Is he still alive the day? Could he be sittin doon right noo somewhere in Bavaria, telling his ain grandchildren how he fought for an hour wi a crazy British sojur?”

His eye glazed over as he stared into the fire. I think I saw him wipe away a tear but I said nothing and I too gazed into the fire.

“Such a waste,” he whispered. “Such a waste ae gid young lives.”

To me, my Granda was a hero.

When I was twelve, I was playing football with my fellow street urchins one warm Sunday evening when I spotted him walking along the street with that familiar stoop and his hands clasped behind his back. He sported the usual battered old bunnet and worn-out hounds tooth jacket as he walked slowly and nonchalantly, seemingly without a care in the world. I called out his name and he stopped and, on recognising me, raised his arm to wave. He stood for some minutes watching the game, occasionally shouting words of encouragement.

“Good baw Thomas . . . gae it tae Thomas . . . great goal Thomas . . .”

At half-time I went over to speak to him.

“Are ye gaun tae oor hoose Granda?”

I wiped beads of perspiration from my face.

“Naw son,” he replied. “Jist oot furra walk n a bit ae fresh air.”

He pulled a white paper bag from his pocket and held it towards me.

“Hiv a mint Thomas.”

“Aw ta Granda.”

He always carried a supply of rock hard white mints.

“Ye lookin furrit tae Hampden oan Setterday then?” he said, after waiting for his dentures to negotiate the hard sweet.

“Aye Granda, a cannae wait. Ma first cup final.”

“A can still remember ma first final.”

He looked at his feet and shook his head as he spoke.

“Celtic’n Rangers it wiz. A well remember no bein able tae sleep the night afore, a bit like yersel Thomas.”

“Am glad it’s Dunfermline no Rangers this time,” I said. “Mum widnae lit me go if it wiz Rangers.”

“Aye it’s a shame aw this bigotry nonsense still goes on. A wish they could enjoy the rivalry withoot aw that baggage. Ach well, that’s religion fur ye. Mair folks’ve died oer the heid ae religion than onythin else in this world ah’ll tell ye.”

My friends were now preparing to resume the match.

“A better git movin,” I told him.

“Aye, ah’ll away then Thomas,” he said. “See ye soon then.”

“Aye, see ye Granda. Take care.”

I moved towards my friends but was stopped in my tracks.

“Jist a wee minute Thomas,” he called after me and I turned to face him once again.

“Whit is it Granda?”

“If onybody asks,” he said. “If yer Nana asks like . . . well . . . ye never seen me, right?”

I looked at him in silence.

“If Nana says onythin, don’t lit ona ye seen me, right?”

“Sure Granda, a wullnae say a word.”

I didn’t ask for an explanation but he offered me one anyway.

“It’s jist that, ah’m supposed tae be it six o’clock Mass. Couldnae be bothered gaun. She’ll gae me merry hell if she funs oot.”

“Nae problem Granda,” I reassured him. “She’ll no hear it fae me.”

“Good lad,” he smiled warmly. “Go on then. Enjoy yer gemme.”

I felt a great surge of pride in the realisation that my Granda, the great hero, had shared a secret with me and that my silence would protect him from a nagging, or worse. At the same time I wondered how it was that my Granda, who had fought hand-to-hand combat with a German soldier for more than an hour; who had lost an eye under the piercing blow of a German bayonet; who had stood up to the Protestant gangs who stoned him and his family as they walked to Mass every Sunday morning in Edwardian Motherwell; who had stood shoulder to shoulder with his fellow workers and battled with the riot police during the General Strike; how could this great hero be walking the streets alone, rather than tell his wife, my Nana, that he couldn’t be bothered going to Mass?

Three years later, just days after my Nana’s funeral, my Granda was telling me what a wonderful and strong woman she was. For the first time I asked him about that Sunday night and he told me he remembered it well.

“A bet ye were wonderin why a couldnae jist tell ur a wisnae gaun tae the chapel.”

I admitted that the thought had crossed my mind.

“When ye git tae oor age Thomas, me n yer Nana a mean. When ye git tae oor age, ye start thinkin aboot death n'at. No the actual dyin. No, a mean the passin oan, ye know, whit’s waitin fur ye oan the other side.”

“Like Heaven n Hell?”

“Aye, that’s right. It’s jist that, a havnae believed ony ay it since a wiz your age.”

“Ye mean ye don’t believe in God?”

“Well, it’s no as simple as that. It’s jist this gaun tae Mass oan a Sunday thing. A jist don’t think it’s such a big deal if ye decide tae gae it a miss noo n again. Bit tae listen tae yer Nana, it wiz hellfire n eternal damnation fur me if a so much as mentioned stayin in the hoose when a should be tt the chapel. The thing is Thomas, she believed in it aw the way, an if a committed a mortal sin, as she seen it like, bay missin Mass, she’d jist worry herself sick that ah’d drap doon deid n go tae Hell before a hud the chance tae go tae confession or change ma underpants. She even telt me ah’d spoil it fur hur cos she’d go tae Heaven n couldnae enjoy it knowin a wiz burnin away in the Bad Fire.”

“So ye don’t believe in the Bad Fire eether?”

“Mibbe there is a Bad Fire, mibbe no Thomas, bit if there is, a cannae believe God wid pit some'dy there jist fur missin Mass oan a Sunday. Bank robbers n murderers aye, bit no fur missin Mass or tellin the odd white lie or usin bad language or stealin a loaf ae breed or, or whitever. Surely the God Nana an yer mother worship every Sunday cannae be that cruel.”

To me, my Granda was now a hero and a sinner.

“So ye preferred a quiet life rather than upset her.”

“Aye Thomas, that’s it exactly,” he said with a smile. “That n the fact she wiz English intae the bargain.”

My Granda was a great Rabbie Burns fanatic. He could, and often did, recite the whole of Tam O’Shanter from start to finish. Though he was a Burns fanatic, he wasn’t boring with it, and didn’t ram it down our throats. He would quote the great man in everyday life and always in proper context.

My friend Owen Kelly and I spent hours preparing for the school Christmas dance. Our Lady’s High School was an all-boys establishment, a legacy of the traditional thinking of the Catholic hierarchy in the first half of the twentieth Century. The more intelligent Catholic boys were not to be distracted from their education by the testosterone challenging proximity of girls in the classroom. So the annual arrangement was that girls from the Catholic Convent School would be bussed in for the evening, lest we should be tempted by the apparently greater evil of dancing with boys.

As I stood before my mother and my Nana, my curly hair caked in brylcreem in a fruitless attempt at straightening it in defiance of the laws of both physics and physiology; my winkle-picker shoes shining proudly following their first polishing since the previous Christmas; my face and neck blotchy red and stinging under the cheap and malodorous after shave; and the top three buttons of my shirt unfastened to reveal an expanse of scrawny white skin under the merest sprinkling of fluffy chest hair, I felt like I was being briefed in advance of a dangerous and important mission.

“Button your shirt up Thomas or you’ll catch the death of cold.”

“Comb your hair Thomas. It’s sticking up at the back.”

“Don’t let any of those Convent lassies drag you out the school.”

Chance would be a fine thing.

“And if they kiss you, keep your mouth shut.”

No fear. If I get kissed, I’ll not be telling any of you lot.

They started prodding me, tugging at my collar, buttoning my shirt, patting my hair.

“What’s wrong with curls anyway Thomas? You shouldn’t try and hide them.”

“Aye, it doesn’t look natural son.”

Oh wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us

Tae see oursels as others see us !

Quoth Granda from behind his Motherwell Times.

“Just you read your paper and mind your own business,” said Nana.

“And don’t be late Thomas. Don’t get carried away and miss the last bus.”

We think na on the lang Scots miles,

The mosses, waters, slaps and styles,

That lie between us and our hame,

Where sits our sulky sullen dame,

Gathering her brows like gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

At the party, a girl called Elspeth dragged me out the school. She led me by the hand round to the dark side of the ancient building. My jacket was still hanging on a peg in the cloakroom and I shivered in my shirt sleeves. Elspeth leaned back against the wall and pulled me towards her. She wrapped her arms around my neck and proceeded to kiss me ferociously. After a few minutes she let me up for air and rested her head on my shoulder. Soon she was licking the inside of my left ear, which sounded like I was being eaten alive by a giant slug, and felt like it too. Then, with a swift movement of the head, she pushed her soft wet tongue into my mouth where it wriggled around like a hooked salmon. Gasping for air and wishing to rid the inside of my mouth of the nauseatingly fleshy intrusion, not to mention the strong taste of fresh ear wax, I pushed her away and, after gulping down a large portion of air and exhaling at length, I wiped my lips with the sleeve of my shirt.

“Whit’s wrang wi you,” I said. “Lost yer chewin gum?

“McLaughlin.”

I was rescued by the gruff voice of Mr Healy, my English teacher.

I pushed Elspeth away and watched as Mr Healy peered round the corner.

“Put that young lady down and get back indoors,” he commanded. “Now.”

I was only fourteen then. It was the last time I was happy to be rescued from the clutches of an amorous young lady.

In the Summer of 65 my Granda took me, my Ma and my Nana to Glasgow to see The Sound of Music. I set off in trepidation as the whole idea of such an outing filled me with feelings of horror and embarrassment. I was eleven years old and wanted to be playing football or kick-the-can or chap-door-run-away with my friends. My street credibility took a nosedive as I was dragged off on the big bus to watch a film about singing nuns in some far-off country full of hills and girls with flowery frocks and men in leather shorts.

The venture was organised by Father Logue, the parish priest of St Luke’s. He had placed an advert on the notice board at the back of the chapel, requesting that parishioners should append names and numbers by a certain closing date. On the big night we all duly gathered in the chapel hall - me and a collection of people, whose ages ranged from an elderly twenty-five to an ancient eighty-eight.

My Granda reckoned I would enjoy the picture because he perceived that I had, at a very early age, shown a healthy interest in music. He owned a very impressive radiogram in those days. It resembled a shiny wooden box, rather like a child’s coffin, on four wooden legs. When you opened the lid of the box, there was on the right hand side a radio set with all manner of buttons to push and knobs to turn. A glass panel had various markings painted over it, with lines and numbers and strange words such as Luxemburg, Hilvershum and Vienna. To the left was a turntable which spun at various speeds round a vertical six inch metal spindle which held up to eight vinyl records, dropping each in turn on to the turntable, or the previous record, where the arm, which seemed to have a mind of its own, would retreat and, when it saw that the next record had been dropped into place, would swing back, stopping at a precise point at the edge of the now spinning record, before slowly and gently lowering itself and the needle on to the black, shining disc and, after a few hesitant but rhythmic crackles, my ears would be filled with the sound of music.

I used to spend hours lying on my back with my head beneath the body of the radiogram, between the two front legs, listening to record after record, but if my Granda reckoned that filling my ears with a constant diet of Frank Ifield, Perry Como, Frank Sinatra and The Bachelors represented a healthy interest in music then who am I to argue?

The big bus took an hour to trundle its way through Lanarkshire towards the big city. Father Logue passed the time by moving slowly along the passageway, spending a few moments with his parishioners. I spent the whole time with my nose against the window as I took in the sights and sounds of the countryside, then small towns, more countryside, until the towns got more frequent and bigger and the countryside got sparser and before long we were rolling noisily through the east end of Glasgow. I knew we were in Glasgow when my Granda excitedly pointed out the four gigantic, towering pylons which were the floodlights of Celtic Football Ground. For many years to come I would feel time and time again that familiar feeling of awe and breathless excitement as I saw the very same floodlights, shining like a beacon, growing nearer and nearer as our bus approached on match days.

The cinema was packed to capacity and the audience was peppered here and there with a collection of priests and nuns of all shapes and sizes, giving the auditorium the feel of the main stand at Celtic Park. Some months earlier, on a Saturday morning, I had queued outside the Rex Cinema in Motherwell, along with a hundred or so excited youngsters, waiting to see One Million Years BC. I began to imagine a hundred priests and nuns lining up outside the picture house on the first showing of The Sound of Music. This set me wondering whether the priests got in for nothing, like they did at Celtic matches.

My Granda once told me how he and my uncle Tommy spent much time and effort designing two makeshift dog collars which they wore with suitably adjusted black shirts and jumpers. They managed to see six matches, free of charge, before my Granda forgot himself and rose to his feet to berate a linesman with language that would make a coal miner blush. As a policeman came to eject him, uncle Tommy stopped him with a right hook which sent him sprawling across three rows of seats and about half a dozen spectators, at least two of whom were bona fide priests. Their scam was rumbled and, after a weekend in the cells and a Monday morning visit to the Sheriff Court and a ten shillings fine, they had to walk the fifteen miles or so back to Motherwell.

They sang Irish rebel songs as they sauntered through the mining village of Viewpark, where they got into a fight with a trio of local Orangemen and were promptly arrested yet again. The Motherwell Celtic Supporters Club organised a whip-round and a committee member was despatched to bail them out and return them to the safety to their families. Safety? My Granda suffered a headache for four days, courtesy of my Nana’s rolling pin.

The incessant babble which filled the auditorium subsided as the house lights were dimmed. Several rows behind me a mother berated her young daughter in hushed but audible tones. “For heaven’s sake Angela,” she cried in exasperation. “Why wait till the film starts before wanting a pee?”

I burst out laughing and all around me, a dozen grown-ups said, “Ssshhh!” in perfect harmony.

“Don’t you tell my grandson to Ssshhh,” Nana snapped back.

“But ah’m burstin,” pleaded Angela, who sounded like she was straining to hold back the torrent for a few seconds longer.

“Ssshhh!”

On screen, an exuberant fresh-faced lady was running up a grassy hill under a clear blue sky. The music began to rise with her. First, soft strings, like a breeze blowing through your hair. The lady reached a certain point before raising her arms and spinning round in circles as the music rose to a crescendo. She smiled a most wonderful smile before breaking into song. Her voice was exquisite and the music and the colours were mesmerising. From that moment I was hooked. For three hours I was transported to the sights and sounds of Salzburg and the Tyrolean Mountains. You could almost smell the edelweiss and taste the clear, fresh air. I saw the splendour of the castle as it looked down majestically over the town, little knowing that thirty years later I’d be standing at the walls of that very castle, gazing down at the colourful and picturesque town that was the birthplace of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

I sat in silent awe until the very end. I was spellbound by the colours, the breathtaking scenery, the beautiful children, the acting, the singing, the music, the songs, the dancing. It was a whole new world for me. Oh, and I fell head over heels in love with Brigitta.

On the journey home, we all sang the songs from the film, led by Mrs McTaggart, who seemed to know all the words as she stood in the middle of the passageway, grinning widely and swaying from side to side as she conducted the choir. She must have been on some sort of medication, for several times in the cinema I saw her swig from a plastic bottle when no-one else was looking. Even I was so enveloped in the whole atmosphere that I found myself standing on my seat and singing more and more robustly as I became familiar with the songs. I was even seen to wave my arms exuberantly and, before dropping off to sleep that night, the excitement having dissipated somewhat, I remember thinking, was that really me?

Father Logue sat down beside me on the bus and we talked for a while, about the film, school, football and the fact that he was looking to recruit a handful of altar boys and, would I be interested? I wasn’t keen at first but felt unable to refuse a priest so agreed to attend a meeting of all the altar boys after ten o’clock Mass on Sunday.

Next morning, my Granda quickly removed any doubts from my mind.

“Ye should go tae the meeting Thomas,” he enthused. “Becomin an altar boy is quite an honour ye know.”

“I thought ye wernae too keen oan religion,” I reminded him.

“Aye well that’s me Thomas. Ah’m an auld man. You’ve goat yer whole life in front ae ye. Lit me put it this way laddie.”

He moved forward and sat on the edge of his seat and clasped his hands together.

“Whin ye grow up n leave school ye can decide fur yersel, bit while yer in the care o yer mother n father, ye must listen tae them n dae wht they say. Bit apart fae aw that, servin as an altar boy is jist another wan ae those interestin experiences ye meet in life. It’s no every boy thit gits ast ye know. Ye’ll hiv a bit o responsibility in front ae aw those people an it’s aw good experience fur future life. It’ll make ye mentally tougher believe you me, an ye’ll learn a fair bit ae Latin.”

Confeteor Deo omni potente...

I have to confess, he was right.

On Sunday, after ten o’clock Mass, myself and two more new recruits were debriefed by Father Logue, who spent some time putting us at ease and informally talking about the Mass stage by stage and at various points, outlining our duties. We were informed that we would be required to attend several practice sessions over the next few weeks before being allowed to serve a full Mass. We were also supplied with Mass books which contained the priest’s script in black print and the altar boys’ responses in red, all in Latin. We were told to practice at home and to learn the words by heart.

I had to go the full hog.

Each evening I would go to my room, dress in my newly acquired sitan and surplice, kneel on the floor in front of the mirror, hold the Mass book in front of me and, in what my mother, even to this day, describes as the voice of a wailing cat, I recited the whole Latin script from start to finish, only looking at the book when my memory demanded it.

Before long, I was a fully trained altar boy. My whole family turned out on the morning of my first Sunday Mass. Even my Granda the sinner was there. While the priest stood on the pulpit, delivering his sermon to the packed church, the two altar boys were required to sit, facing the congregation, on the carpeted steps leading up to the altar. This I found unnerving, as I imagined all eyes were fixed on me. I began to blush and lowered my head, avoiding the sea of eyes.

Father Logue was lecturing his parishioners on the use of “foul and abusive language”.

“It is the responsibility of every parent,” he said in a loud and commanding voice. “To ensure that their children, given to them by the love of God, are not subjected to cursing and swearing.”

“See mammy, a telt ye,” said a young boy in a high-pitched tone as he tugged at the sleeve of his mother’s coat. “You n ma da hiv tae stoap swearin aw the time.”

Father Logue paused for a few seconds as the rest of the congregation shifted uncomfortably. A few muffled laughs could be heard here and there.

“Be quiet James,” said the boy’s mother, her face now crimson, and I was grateful as all eyes were now on them instead of me.

“Bit ye’re aye shoutin n swearin it each ither.”

“Will you shut up?” she raised her voice which registered panic.

Father Logue continued speaking in an even louder voice, obviously trying to save the woman’s blushes by drowning out her son. I lowered my head again as everything returned to normal. Then I was aware of a commotion in the congregation. I looked up once again to see my Granda, who was sitting in the front pew, doubled up and clutching his stomach. His head was lowered and his shoulders were shaking. I was fearful that something terrible was happening and instantly I felt a weight in the pit of my stomach. After a few seconds, he raised his head and his face was bright red and his whole body trembled as he began to laugh hysterically, tears welling in his eyes.

Father Logue stopped speaking and looked down at my Granda with a most thunderous look. My Nana thumped him on the shoulder with her umbrella, her face as thunderous as the priest’s. I could see that it was a gargantuan effort for him to stop convulsing and after a while, all was quiet again as he sat, head lowered, gritting his teeth and clearly using all his willpower to control his emotions.

“Whit the bliddy hell ur you laughin at y'an aul bugger?” shouted the mother of the small boy.

This sent my Granda sprawling to his knees in a very loud spurt of suppressed laughter. This time there was no stopping him as he got to his feet and edged swiftly along the pew, past giggling children and embarrassed parents. Father Logue watched in silent astonishment and heads turned throughout the congregation as my Granda fled from the chapel, still laughing hysterically and holding his stomach, hotly pursued by my Nana, who was waving her umbrella menacingly. My own and my fellow altar boy’s giggles were brought to an abrupt halt by the look which Father Logue sent in our direction.

I quickly lowered my head and once again avoided the stares of the congregation.

That afternoon, as we all sat down at Nana’s to Sunday dinner of mince’n tatties, we waited for Nana to finish her silent grace. All that is except my Granda.

Some hae meat, and canna eat,

And some wad eat that want it;

But we hae meat and we can eat,

And sae the Lord be thankit.

The next time my Granda entered the chapel was for his own Requiem Mass, less than two years later. He had not been the same after the death of his wife, my Nana, nurse Renwick.

He had recently moved in with us as he was no longer able to care for himself. I knew he was on a downward spiral when, one evening, I heard him shouting from his bedroom. I went in to see him and he said, “Who is it?”

“It’s Thomas,” I replied.

“Aye Thomas, when ye go tae the Shire the ight, tell them am no well.”

The Shire was a colloquialism for the Lanarkshire Steelworks, where my Granda and his son Thomas, my uncle Tommy, worked together many years earlier. I wiped away a tear at the realisation that he thought I was his son and that he was now transported back to his working days.

I told my mother and she asked me to help her undress him and get him into his pyjamas and into bed.

It took some time and effort as his lifeless body moved unprotesting at our prompting. All the while he spoke in riddles and he did not recognise his daughter and grandson.

Yet still I could hear his calling.

O Thou unknown Almighty Cause

Of all my hope and fear !

In whose dread presence, ere an hour,

Perhaps I must appear !

If I have wander’d in those paths

Of life I ought to shun ;

As something, loudly in my breast,

Remonstrates I have done ;

Thou know’st that Thou hast formed me

With passions wild and strong ;

And list’ning to their witching voice

Has often led me wrong.

Where with intention I have err’d,

No other plea I have,

But Thou art good ; and Goodness still

Delighteth to forgive.

My mother looked in on him at regular intervals. I offered to accompany her on more than one occasion, but she would not allow it. I felt sure then that she knew something I didn’t. It was after the sixth or seventh visit, which lasted much longer than the previous visits, that she returned with tears streaming down her face. She held me to her and hugged me tightly. She did not say a word, but her quiet sobs were enough to tell me that my Granda, the hero and sinner, had passed on to the other side, whatever that was.

O Thou, great Governer of all below !

If I may dare a lifted eye to Thee,

Thy nod can make the tempest cease to blow,

And still the tumult of the raging sea ;

With that controlling pow’r assist ev’n me

Those headlong furious passions to confine,

For all unfit I feel my powers to be,

To rule their torrent in th’ allowed line ;

O, aid me with Thy help, Omnipotence Divine!

For his sake, I hoped and prayed that he was wrong and that there was a Heaven, where my Nana would be waiting for him, alongside a German soldier with a welcoming smile and an outstretched hand.

Where sits our sulky sullen dame,

Gathering her brows like gathering storm,

Nursing her wrath to keep it warm.

At the party, a girl called Elspeth dragged me out the school. She led me by the hand round to the dark side of the ancient building. My jacket was still hanging on a peg in the cloakroom and I shivered in my shirt sleeves. Elspeth leaned back against the wall and pulled me towards her. She wrapped her arms around my neck and proceeded to kiss me ferociously. After a few minutes she let me up for air and rested her head on my shoulder. Soon she was licking the inside of my left ear, which sounded like I was being eaten alive by a giant slug, and felt like it too. Then, with a swift movement of the head, she pushed her soft wet tongue into my mouth where it wriggled around like a hooked salmon. Gasping for air and wishing to rid the inside of my mouth of the nauseatingly fleshy intrusion, not to mention the strong taste of fresh ear wax, I pushed her away and, after gulping down a large portion of air and exhaling at length, I wiped my lips with the sleeve of my shirt.

“Whit’s wrang wi you,” I said. “Lost yer chewin gum?

“McLaughlin.”

I was rescued by the gruff voice of Mr Healy, my English teacher.

I pushed Elspeth away and watched as Mr Healy peered round the corner.

“Put that young lady down and get back indoors,” he commanded. “Now.”

I was only fourteen then. It was the last time I was happy to be rescued from the clutches of an amorous young lady.

In the Summer of 65 my Granda took me, my Ma and my Nana to Glasgow to see The Sound of Music. I set off in trepidation as the whole idea of such an outing filled me with feelings of horror and embarrassment. I was eleven years old and wanted to be playing football or kick-the-can or chap-door-run-away with my friends. My street credibility took a nosedive as I was dragged off on the big bus to watch a film about singing nuns in some far-off country full of hills and girls with flowery frocks and men in leather shorts.

The venture was organised by Father Logue, the parish priest of St Luke’s. He had placed an advert on the notice board at the back of the chapel, requesting that parishioners should append names and numbers by a certain closing date. On the big night we all duly gathered in the chapel hall - me and a collection of people, whose ages ranged from an elderly twenty-five to an ancient eighty-eight.

My Granda reckoned I would enjoy the picture because he perceived that I had, at a very early age, shown a healthy interest in music. He owned a very impressive radiogram in those days. It resembled a shiny wooden box, rather like a child’s coffin, on four wooden legs. When you opened the lid of the box, there was on the right hand side a radio set with all manner of buttons to push and knobs to turn. A glass panel had various markings painted over it, with lines and numbers and strange words such as Luxemburg, Hilvershum and Vienna. To the left was a turntable which spun at various speeds round a vertical six inch metal spindle which held up to eight vinyl records, dropping each in turn on to the turntable, or the previous record, where the arm, which seemed to have a mind of its own, would retreat and, when it saw that the next record had been dropped into place, would swing back, stopping at a precise point at the edge of the now spinning record, before slowly and gently lowering itself and the needle on to the black, shining disc and, after a few hesitant but rhythmic crackles, my ears would be filled with the sound of music.

I used to spend hours lying on my back with my head beneath the body of the radiogram, between the two front legs, listening to record after record, but if my Granda reckoned that filling my ears with a constant diet of Frank Ifield, Perry Como, Frank Sinatra and The Bachelors represented a healthy interest in music then who am I to argue?

The big bus took an hour to trundle its way through Lanarkshire towards the big city. Father Logue passed the time by moving slowly along the passageway, spending a few moments with his parishioners. I spent the whole time with my nose against the window as I took in the sights and sounds of the countryside, then small towns, more countryside, until the towns got more frequent and bigger and the countryside got sparser and before long we were rolling noisily through the east end of Glasgow. I knew we were in Glasgow when my Granda excitedly pointed out the four gigantic, towering pylons which were the floodlights of Celtic Football Ground. For many years to come I would feel time and time again that familiar feeling of awe and breathless excitement as I saw the very same floodlights, shining like a beacon, growing nearer and nearer as our bus approached on match days.

The cinema was packed to capacity and the audience was peppered here and there with a collection of priests and nuns of all shapes and sizes, giving the auditorium the feel of the main stand at Celtic Park. Some months earlier, on a Saturday morning, I had queued outside the Rex Cinema in Motherwell, along with a hundred or so excited youngsters, waiting to see One Million Years BC. I began to imagine a hundred priests and nuns lining up outside the picture house on the first showing of The Sound of Music. This set me wondering whether the priests got in for nothing, like they did at Celtic matches.

My Granda once told me how he and my uncle Tommy spent much time and effort designing two makeshift dog collars which they wore with suitably adjusted black shirts and jumpers. They managed to see six matches, free of charge, before my Granda forgot himself and rose to his feet to berate a linesman with language that would make a coal miner blush. As a policeman came to eject him, uncle Tommy stopped him with a right hook which sent him sprawling across three rows of seats and about half a dozen spectators, at least two of whom were bona fide priests. Their scam was rumbled and, after a weekend in the cells and a Monday morning visit to the Sheriff Court and a ten shillings fine, they had to walk the fifteen miles or so back to Motherwell.

They sang Irish rebel songs as they sauntered through the mining village of Viewpark, where they got into a fight with a trio of local Orangemen and were promptly arrested yet again. The Motherwell Celtic Supporters Club organised a whip-round and a committee member was despatched to bail them out and return them to the safety to their families. Safety? My Granda suffered a headache for four days, courtesy of my Nana’s rolling pin.

The incessant babble which filled the auditorium subsided as the house lights were dimmed. Several rows behind me a mother berated her young daughter in hushed but audible tones. “For heaven’s sake Angela,” she cried in exasperation. “Why wait till the film starts before wanting a pee?”

I burst out laughing and all around me, a dozen grown-ups said, “Ssshhh!” in perfect harmony.

“Don’t you tell my grandson to Ssshhh,” Nana snapped back.

“But ah’m burstin,” pleaded Angela, who sounded like she was straining to hold back the torrent for a few seconds longer.

“Ssshhh!”

On screen, an exuberant fresh-faced lady was running up a grassy hill under a clear blue sky. The music began to rise with her. First, soft strings, like a breeze blowing through your hair. The lady reached a certain point before raising her arms and spinning round in circles as the music rose to a crescendo. She smiled a most wonderful smile before breaking into song. Her voice was exquisite and the music and the colours were mesmerising. From that moment I was hooked. For three hours I was transported to the sights and sounds of Salzburg and the Tyrolean Mountains. You could almost smell the edelweiss and taste the clear, fresh air. I saw the splendour of the castle as it looked down majestically over the town, little knowing that thirty years later I’d be standing at the walls of that very castle, gazing down at the colourful and picturesque town that was the birthplace of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

I sat in silent awe until the very end. I was spellbound by the colours, the breathtaking scenery, the beautiful children, the acting, the singing, the music, the songs, the dancing. It was a whole new world for me. Oh, and I fell head over heels in love with Brigitta.

On the journey home, we all sang the songs from the film, led by Mrs McTaggart, who seemed to know all the words as she stood in the middle of the passageway, grinning widely and swaying from side to side as she conducted the choir. She must have been on some sort of medication, for several times in the cinema I saw her swig from a plastic bottle when no-one else was looking. Even I was so enveloped in the whole atmosphere that I found myself standing on my seat and singing more and more robustly as I became familiar with the songs. I was even seen to wave my arms exuberantly and, before dropping off to sleep that night, the excitement having dissipated somewhat, I remember thinking, was that really me?

Father Logue sat down beside me on the bus and we talked for a while, about the film, school, football and the fact that he was looking to recruit a handful of altar boys and, would I be interested? I wasn’t keen at first but felt unable to refuse a priest so agreed to attend a meeting of all the altar boys after ten o’clock Mass on Sunday.

Next morning, my Granda quickly removed any doubts from my mind.

“Ye should go tae the meeting Thomas,” he enthused. “Becomin an altar boy is quite an honour ye know.”

“I thought ye wernae too keen oan religion,” I reminded him.

“Aye well that’s me Thomas. Ah’m an auld man. You’ve goat yer whole life in front ae ye. Lit me put it this way laddie.”

He moved forward and sat on the edge of his seat and clasped his hands together.

“Whin ye grow up n leave school ye can decide fur yersel, bit while yer in the care o yer mother n father, ye must listen tae them n dae wht they say. Bit apart fae aw that, servin as an altar boy is jist another wan ae those interestin experiences ye meet in life. It’s no every boy thit gits ast ye know. Ye’ll hiv a bit o responsibility in front ae aw those people an it’s aw good experience fur future life. It’ll make ye mentally tougher believe you me, an ye’ll learn a fair bit ae Latin.”

Confeteor Deo omni potente...

I have to confess, he was right.

On Sunday, after ten o’clock Mass, myself and two more new recruits were debriefed by Father Logue, who spent some time putting us at ease and informally talking about the Mass stage by stage and at various points, outlining our duties. We were informed that we would be required to attend several practice sessions over the next few weeks before being allowed to serve a full Mass. We were also supplied with Mass books which contained the priest’s script in black print and the altar boys’ responses in red, all in Latin. We were told to practice at home and to learn the words by heart.

I had to go the full hog.

Each evening I would go to my room, dress in my newly acquired sitan and surplice, kneel on the floor in front of the mirror, hold the Mass book in front of me and, in what my mother, even to this day, describes as the voice of a wailing cat, I recited the whole Latin script from start to finish, only looking at the book when my memory demanded it.

Before long, I was a fully trained altar boy. My whole family turned out on the morning of my first Sunday Mass. Even my Granda the sinner was there. While the priest stood on the pulpit, delivering his sermon to the packed church, the two altar boys were required to sit, facing the congregation, on the carpeted steps leading up to the altar. This I found unnerving, as I imagined all eyes were fixed on me. I began to blush and lowered my head, avoiding the sea of eyes.

Father Logue was lecturing his parishioners on the use of “foul and abusive language”.

“It is the responsibility of every parent,” he said in a loud and commanding voice. “To ensure that their children, given to them by the love of God, are not subjected to cursing and swearing.”

“See mammy, a telt ye,” said a young boy in a high-pitched tone as he tugged at the sleeve of his mother’s coat. “You n ma da hiv tae stoap swearin aw the time.”

Father Logue paused for a few seconds as the rest of the congregation shifted uncomfortably. A few muffled laughs could be heard here and there.

“Be quiet James,” said the boy’s mother, her face now crimson, and I was grateful as all eyes were now on them instead of me.

“Bit ye’re aye shoutin n swearin it each ither.”

“Will you shut up?” she raised her voice which registered panic.

Father Logue continued speaking in an even louder voice, obviously trying to save the woman’s blushes by drowning out her son. I lowered my head again as everything returned to normal. Then I was aware of a commotion in the congregation. I looked up once again to see my Granda, who was sitting in the front pew, doubled up and clutching his stomach. His head was lowered and his shoulders were shaking. I was fearful that something terrible was happening and instantly I felt a weight in the pit of my stomach. After a few seconds, he raised his head and his face was bright red and his whole body trembled as he began to laugh hysterically, tears welling in his eyes.

Father Logue stopped speaking and looked down at my Granda with a most thunderous look. My Nana thumped him on the shoulder with her umbrella, her face as thunderous as the priest’s. I could see that it was a gargantuan effort for him to stop convulsing and after a while, all was quiet again as he sat, head lowered, gritting his teeth and clearly using all his willpower to control his emotions.

“Whit the bliddy hell ur you laughin at y'an aul bugger?” shouted the mother of the small boy.

This sent my Granda sprawling to his knees in a very loud spurt of suppressed laughter. This time there was no stopping him as he got to his feet and edged swiftly along the pew, past giggling children and embarrassed parents. Father Logue watched in silent astonishment and heads turned throughout the congregation as my Granda fled from the chapel, still laughing hysterically and holding his stomach, hotly pursued by my Nana, who was waving her umbrella menacingly. My own and my fellow altar boy’s giggles were brought to an abrupt halt by the look which Father Logue sent in our direction.

I quickly lowered my head and once again avoided the stares of the congregation.

That afternoon, as we all sat down at Nana’s to Sunday dinner of mince’n tatties, we waited for Nana to finish her silent grace. All that is except my Granda.

Some hae meat, and canna eat,

And some wad eat that want it;

But we hae meat and we can eat,

And sae the Lord be thankit.

The next time my Granda entered the chapel was for his own Requiem Mass, less than two years later. He had not been the same after the death of his wife, my Nana, nurse Renwick.

He had recently moved in with us as he was no longer able to care for himself. I knew he was on a downward spiral when, one evening, I heard him shouting from his bedroom. I went in to see him and he said, “Who is it?”

“It’s Thomas,” I replied.

“Aye Thomas, when ye go tae the Shire the ight, tell them am no well.”

The Shire was a colloquialism for the Lanarkshire Steelworks, where my Granda and his son Thomas, my uncle Tommy, worked together many years earlier. I wiped away a tear at the realisation that he thought I was his son and that he was now transported back to his working days.

I told my mother and she asked me to help her undress him and get him into his pyjamas and into bed.

It took some time and effort as his lifeless body moved unprotesting at our prompting. All the while he spoke in riddles and he did not recognise his daughter and grandson.

Yet still I could hear his calling.

O Thou unknown Almighty Cause

Of all my hope and fear !

In whose dread presence, ere an hour,

Perhaps I must appear !

If I have wander’d in those paths

Of life I ought to shun ;

As something, loudly in my breast,

Remonstrates I have done ;

Thou know’st that Thou hast formed me

With passions wild and strong ;

And list’ning to their witching voice

Has often led me wrong.

Where with intention I have err’d,

No other plea I have,

But Thou art good ; and Goodness still

Delighteth to forgive.

My mother looked in on him at regular intervals. I offered to accompany her on more than one occasion, but she would not allow it. I felt sure then that she knew something I didn’t. It was after the sixth or seventh visit, which lasted much longer than the previous visits, that she returned with tears streaming down her face. She held me to her and hugged me tightly. She did not say a word, but her quiet sobs were enough to tell me that my Granda, the hero and sinner, had passed on to the other side, whatever that was.

O Thou, great Governer of all below !

If I may dare a lifted eye to Thee,

Thy nod can make the tempest cease to blow,

And still the tumult of the raging sea ;

With that controlling pow’r assist ev’n me

Those headlong furious passions to confine,

For all unfit I feel my powers to be,

To rule their torrent in th’ allowed line ;

O, aid me with Thy help, Omnipotence Divine!

For his sake, I hoped and prayed that he was wrong and that there was a Heaven, where my Nana would be waiting for him, alongside a German soldier with a welcoming smile and an outstretched hand.

No comments:

Post a Comment